If you have been living with chronic pain, you may have heard the phrase "it is all in your head." It is perhaps the most frustrating, invalidating, and misunderstood sentence in the medical lexicon. It implies that your pain is imaginary, made up, or a sign of weakness.

At Destiny Health, we want to set the record straight: Your pain is 100% real. However, the location where that pain is constructed does indeed include the brain. This distinction is vital. It is not that you are imagining the pain; it is that your brain may have become hyper-efficient at producing it.

To understand why chronic pain may persist long after tissues have healed, we must look away from the muscles and joints for a moment and look toward the complex wiring of the central nervous system (which is comprised of the brain plus the spinal cord). We need to talk about Neurotags.

Understanding Neurotags is often the "lightbulb moment" for our clients. It can go some way towards explaining why pain can flare up due to stress, why old injuries hurt when the weather changes, and, most importantly, how we can retrain the system to find relief.

What is a Neurotag?

The human brain contains approximately 86 billion neurons (nerve cells). These cells constantly communicate with one another, sending electrical and chemical signals at lightning speed.

However, neurons rarely work in isolation. They work in teams. When you perform an action, think a thought, or experience a sensation, a specific network of neurons fires simultaneously. This collaborative network is what modern pain scientists, such as Professor Lorimer Moseley and David Butler, call a Neurotag.

Think of a Neurotag like an orchestra playing a symphony.

-

To play "Beethoven’s 5th," you need the violins, the cellos, the percussion, and the brass section all playing their specific notes at the exact same time.

-

Individually, a single violin pluck isn't the song. It is only when the whole group activates together that the "output" (the music) is created.

In the brain, everything you experience is an output of a Neurotag.

-

There is a Neurotag for the smell of coffee.

-

There is a Neurotag for the movement of lifting your arm.

-

There is a Neurotag for the feeling of happiness.

-

And, crucially, there is a Pain Neurotag.

The fundamental rule of neuroscience, coined by Donald Hebb in 1949, is this: "Cells that fire together, wire together." The more often a specific Neurotag is activated, the stronger, faster, and more efficient that network becomes.

The Components of a Pain Neurotag

In the past, we believed that pain was a simple system: you hit your thumb with a hammer, a signal travels up a wire to the brain, and a "pain bell" rings. We now know this is incorrect.

Pain is not JUST an input; it is an output as well. It is a decision made by the brain based on the perception of threat.

When a Pain Neurotag fires, it doesn't just involve the sensory part of the brain (which tells you where it hurts). A Pain Neurotag is a massive, widespread network that borrows neurons from many different areas of the brain, including:

-

Sensory Areas: "My lower back hurts."

-

Motor Areas: "I need to tense my muscles to protect the back."

-

Emotional Areas (Amygdala/Limbic System): "I am afraid of this pain; it makes me anxious."

-

Memory Centres (Hippocampus): "This feels like when I herniated a disc five years ago."

-

Cognitive Areas: "I won't be able to go to work tomorrow."

This interconnectivity is why chronic pain is so exhausting. When the Pain Neurotag fires, it isn't just creating a physical sensation; it is often simultaneously activating fear, memory, stress, and motor changes. The orchestra is playing a very loud, chaotic, and demanding piece of music.

We see examples of this in sports, where the athlete can continue to compete at a high level, while the meaning of competition is strong, while the adrenaline is firing, and after the event they can barely walk. The emotional and cognitive areas appear to have overridden the sensory and motor regions.

Conversely, we see people who have been injured at work continue to experience crippling pain, fear and anxiety long after the injuries have resolved on imaging. In these instances, it appears as though their emotional centres are highly engaged in a never ending pain-fear-anxiety loop.

How Neurotags Become "Sticky" in Chronic Pain

In an acute injury, say, a sprained ankle, the Pain Neurotag fires to protect you. It stops you from walking on the ankle so it can heal. As the tissue heals, the threat diminishes, the orchestra quiets down, and the Neurotag fades. However, in chronic pain, the system malfunctions. The tissue heals, but the Neurotag remains sensitised.

Because "cells that fire together, wire together," if you have been in pain for months or years, your brain might become an expert at playing the "Pain Song." The threshold for activating this Neurotag drops lower and lower. Eventually, it doesn't take a physical injury to trigger the pain; it only takes a subtle cue that is associated with the network.

This is where the concept of imprecise neurotags or disinhibition comes into play.

1. The Association Game

Imagine that every time you hurt your back, you were bending over to load the dishwasher. Your brain eventually links "bending forward" and "dishwasher" into the Pain Neurotag. Later, simply looking at the dishwasher or thinking about bending over might activate the network enough to produce pain, even if you haven't moved yet. The neurons responsible for visual processing (seeing the dishwasher) have wired themselves to the neurons responsible for pain.

2. Smudging

In a healthy brain, Neurotags are precise. When you move your index finger, a very specific cluster of neurons fires. In chronic pain, these maps become "smudged." The brain loses the ability to define distinct boundaries. The Neurotag for "lower back movement" might bleed into the Neurotag for "hip movement" or even "emotional stress." This is why chronic pain often spreads or moves around. The orchestra has lost its sheet music and is playing loudly and messy, engaging instruments that shouldn't be playing. It’s a bit like referred pain, which occurs naturally, such as rotator cuff pain being felt in the lateral (outer) arm, however it’s on overdrive, so pain is felt in the entire upper limb, neck and upper back.

Why Is This Good News? (The Power of Neuroplasticity)

Reading this, you might feel discouraged, thinking that your brain is hardwired for pain. But there is a massive silver lining.

If the brain can learn pain, the brain can unlearn pain.

Just as neuroplasticity (the brain's ability to change) allows Neurotags to become sensitised, it also allows us to dismantle them. This process is often called desensitisation or synaptic pruning.

If "cells that fire together, wire together," the inverse is also true: "Cells that fire apart, wire apart."

If we can break the link between the movement (e.g., bending over) and the pain output, the Neurotag weakens. The orchestra slowly forgets how to play the "Pain Song."

How We Treat Sensitive Neurotags

At Destiny Health, our approach to physiotherapy and chronic pain management is built on this neuroscience. We don't just treat the tissue (which has often already healed); we treat the Neurotag.

Here is how we do it:

1. Pain Neuroscience Education (PNE)

Simply understanding what a Neurotag is often acts as a potent painkiller. When you realise that your pain is a result of a sensitised system rather than simply a crumbling body, the "fear" component of the Neurotag is often reduced. When you take the fear away, the orchestra loses its conductor. The threat level drops, and the pain volume often decreases.

The Example: "The Sensitive House Alarm"

The Metaphor Imagine you live in a lovely house that is protected by a high-tech security alarm system.

-

In a normal scenario: If a burglar throws a brick through the window, the alarm goes off. It screams loudly to tell you there is a threat. You call the police, they catch the burglar, you fix the window, and the alarm resets. This is acute pain (like spraining an ankle). The alarm worked perfectly: it told you there was damage, and you protected the house.

-

In a chronic pain scenario: Now, imagine that after the burglary, the alarm system’s computer glitches. The wires get crossed and the sensors become hyper-sensitive. The window is fixed, and the burglar is long gone, but the alarm system remains on "high alert."

-

Now, a leaf blows against the window? The alarm goes off.

-

A cat walks past the front door? The alarm goes off.

-

The postman drops a letter? The alarm goes off.

The Application (The "Aha!" Moment) In this scenario, when the alarm is ringing (the pain), is the sound real? Yes. It is loud, deafening, and distressing. You are not imagining the noise.

However, is there a burglar? No. The window is safe. The house is secure.

The Lesson for the Patient PNE teaches the client that their chronic pain is the sensitive alarm, not a sign that a "burglar" (damage) is breaking their spine every time they bend over.

-

Old Belief: "My back hurts when I bend; therefore, I am damaging my spine." -> Result: Fear, avoidance, more pain.

-

New PNE Belief: "My back hurts when I bend because my alarm system is sensitive. The tissue is strong, but the sensors are just reacting to the 'leaf' (movement)." Result: Confidence, gradual movement, desensitisation.

2. Graded Exposure

We have to teach your brain that movement is safe. We do this through "Graded Exposure." If bending all the way down triggers the Neurotag, we don't force it. We might start with simply tilting the pelvis, or visualising the movement (which fires the motor neurons without the sensory feedback). We slowly increase the demand, proving to the brain, step by step, that no damage is occurring. We are slowly teasing apart the neurons that link "movement" to "pain."

The Example: "The Laundry Basket Fear"

The Scenario Imagine a patient named Sarah who has chronic lower back pain. Her "trigger" is bending forward. She hasn't picked up a laundry basket from the floor in two years because her brain predicts pain and danger the moment she thinks about that movement. Her "Bending Neurotag" is extremely sensitive.

The Graded Exposure Process Instead of forcing Sarah to pick up the basket immediately (which would trigger a flare-up), the physiotherapist breaks the activity down into a "ladder" of safety. The goal is to perform the activity below the threshold of a flare-up, teaching the brain that the movement is safe.

-

Step 1: Visualisation (The Brain Game)

-

Sarah sits in a chair and closes her eyes. She imagines herself bending down to pick up the basket without pain.

-

Why: Functional MRI scans show that imagining a movement activates many of the same brain areas (Neurotags) as doing it, but without the sensory input from the back. This starts to "dim" the alarm.

-

Step 2: Reduced Gravity (The Child’s Pose)

-

Sarah gets on her hands and knees (quadruped position) and gently rocks her bum back towards her heels.

-

Why: This mimics the exact same joint angles in the hips and spine as bending over, but because she is horizontal, there is no gravity compressing the spine. The brain accepts this as "safe" because the context is different.

-

Step 3: Raising the Floor (Context Change)

-

We place the laundry basket on a high table (waist height). Sarah practices lifting it just 5cm off the table.

-

Why: She is doing the lifting motion, but she doesn't have to bend her spine yet. She builds confidence that her back muscles can take a load.

-

Step 4: Lowering the Target

-

Over a few weeks, we move the basket to a chair (knee height), then to a low step (shin height).

-

Why: We are slowly exposing the Neurotag to more "threat" (bending deeper), but only moving to the next step once the current step feels safe.

-

Step 5: The Real Thing (Success)

-

Eventually, Sarah lifts the basket from the floor.

The Result: By the time Sarah reaches Step 5, her brain has accumulated hundreds of "reps" of successful, pain-free movement at the previous levels. The Neurotag has been re-wired from "Bending = Danger" to "Bending = Safe."

3. Novel Movement

Neurotags thrive on habit. To break them, we often introduce "novel" movement; moving in ways your brain doesn't expect or recognise. This forces the brain to create new Neurotags for movement that aren't contaminated by the old pain associations. This might involve changing the environment, the speed, or the context of your exercise.

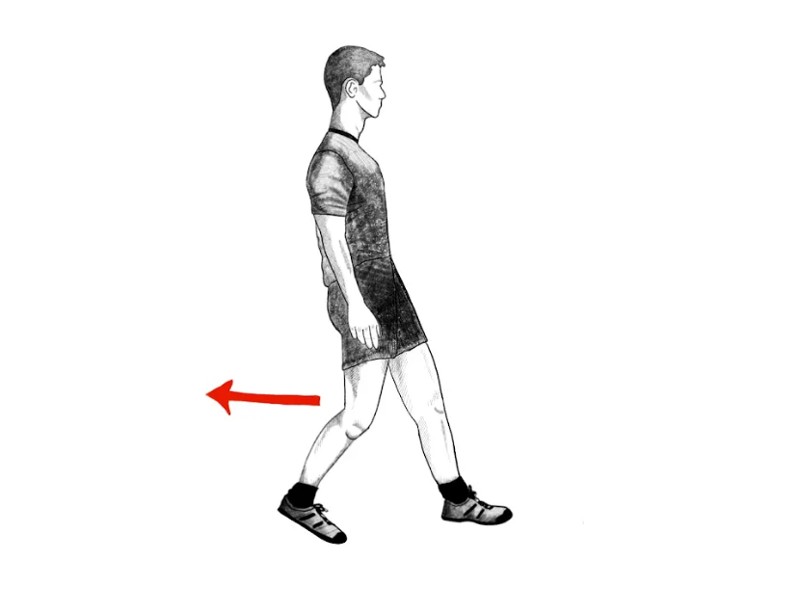

The Example: "Walking Backwards" (Retro-Walking)

The Scenario Consider a patient named "David" who has suffered from chronic knee pain for three years. Every time David takes a normal step forward, his brain predicts threat. His "Walking Neurotag" is intimately linked to his "Pain Neurotag." He limps instinctively, even on days when his knee isn't actually inflamed, because his brain is running a protective habit.

The Novel Movement The physiotherapist asks David to get on a treadmill, but with a twist: he has to walk backwards.

Why This Works Mechanically, the knee is still bending and straightening, and the muscles are still taking the load. However, to the brain, this is a completely different event.

-

Surprise Factor: The brain does not have a stored "history of pain" for walking backwards. It hasn't "wired" this specific weird movement to the pain alarm yet.

-

Focus Shift: Walking backwards requires intense concentration on balance and coordination. The brain is so busy processing this new (novel) motor task that it doesn't have the "bandwidth" to activate the old Pain Neurotag.

-

Result: David often finds he can move his knee through a full range of motion while walking backwards with zero pain.

The Takeaway This proves to David that his knee structure is capable of handling load and movement. The pain was triggered by the familiar pattern (walking forward), not the tissue itself. By using novel movements, we "sneak" exercise past the brain's security system.

4. Addressing the Context

Since emotional stress and environment are part of the Pain Neurotag, we look at the whole picture. Sleep, stress management, and diet all play a role in calming the nervous system. A calmer nervous system holds a higher threshold for firing a Pain Neurotag.

The Example: "The Overflowing Cup" (The Stress Bucket)

The Metaphor We explain to the client that their nervous system is like a cup or a bucket.

-

Water filling the cup: This represents all the stressors in their life: not just physical ones. It includes poor sleep, work deadlines, financial worry, anxiety, and inflammation from diet.

-

The Overflow: When the water reaches the brim and spills over, you experience Pain.

The Scenario Imagine a patient named "Elena" who suffers from chronic migraines and neck tightness. She comes to the clinic convinced that her office chair is causing the pain. However, she notes that sometimes she can sit for 8 hours with no pain, and other days, 20 minutes triggers a migraine. The variable isn't the chair (the physical load); the variable is the context (the water level in the cup).

The Intervention (Addressing the Context) Instead of just changing her chair or massaging her neck, the physiotherapist looks at the other "taps" filling her cup. They discover Elena sleeps only 5 hours a night and drinks 6 coffees a day.

-

Action: We implement a "Sleep Hygiene" protocol (dark room, no screens before bed) to get her to 7 hours of sleep.

-

Action: We introduce a 5-minute breathing exercise (diaphragmatic breathing) to do at her desk to lower cortisol levels.

The Result By improving her sleep and lowering her stress, we lower the water level in the cup. Now, when she sits in the chair (adding a little physical stress), the cup does not overflow. The neck tightness stops, not because we fixed the neck, but because we created a "buffer" in her nervous system so the Neurotag doesn't fire as easily.

Conclusion: You Are The Conductor

Chronic pain can feel like a life sentence, but the science of Neurotags proves that it is not. It is a physiological state of learning: a habit the brain has formed to protect you.

Your brain is the most complex and adaptive structure in the known universe. It learned how to protect you with pain, and with the right guidance, patience, and inputs, it can learn that you are safe again.

The orchestra may be playing a loud, discordant song right now, but you are still the conductor. It is time to teach the band a new tune.

Is Your "Pain Alarm" Stuck On?

If you have been struggling with pain that just won't go away, despite treatments and time, your system might be running on an over-sensitive Neurotag.

At Destiny Health, we specialise in chronic pain rehabilitation that targets the root cause: both in the body and the brain. We don't just guess; we assess with standardised questionnaires, subjective interviews and physical movement screening.

Claim Your Free Assessment Today

We are offering a comprehensive Free Initial Assessment to help you understand your pain story. Let us help you retrain your brain and reclaim your movement.

👉 Book Your Free Assessment at destinyhealth.com.au

Let’s rewrite your pain story together.

References

-

Butler, D. S., & Moseley, G. L. (2013). Explain Pain Supercharged. Noigroup Publications.

-

Hebb, D. O. (1949). The Organization of Behavior: A Neuropsychological Theory. Wiley.

-

Louw, A., Diener, I., Butler, D. S., & Puentedura, E. J. (2011). The effect of neuroscience education on pain, disability, anxiety, and stress in chronic musculoskeletal pain. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 92(12), 2041-2056.

-

Moseley, G. L., & Butler, D. S. (2015). Fifteen years of explaining pain: The past, present, and future. The Journal of Pain, 16(9), 807-813.

-

Nijs, J., Girbés, E. L., Lundberg, M., Malfliet, A., & Sterling, M. (2015). Exercise therapy for chronic musculoskeletal pain: Innovation by altering pain memories. Manual Therapy, 20(1), 216-220.

-

Wall, P. D., & Melzack, R. (1965). Pain mechanisms: A new theory. Science, 150(3699), 971-979.